The French court society of the 18th century seemed to have the same interest in furniture as modern people would do in the cars. Since the birth of modernism in the 20th century, cars and homes had strong conscious relationship.

Machines for living, houses like cars. Le Corbusier’s Citroen House

In 1917, Le Corbusier left Paris from his hometown in Switzerland in 1917, and in 1920 he published the “Esprit Nouveau” and asked the world about his various proposals.

The Russian Revolution takes place (1917), the end of World War I (1919), and Gropius establishes the Bauhaus (1919). A new era was beginning. Corbusier found that the “spirit of the new era” has materialized in industrial products and praised ships, planes and cars.

Among them, a car, a moving room, is similar to a house but it has a value and beauty that a house does not have. Such as rationality that emphasizes functions, mass production by standardization, high product accuracy, freedom of movement, pleasure of speed.

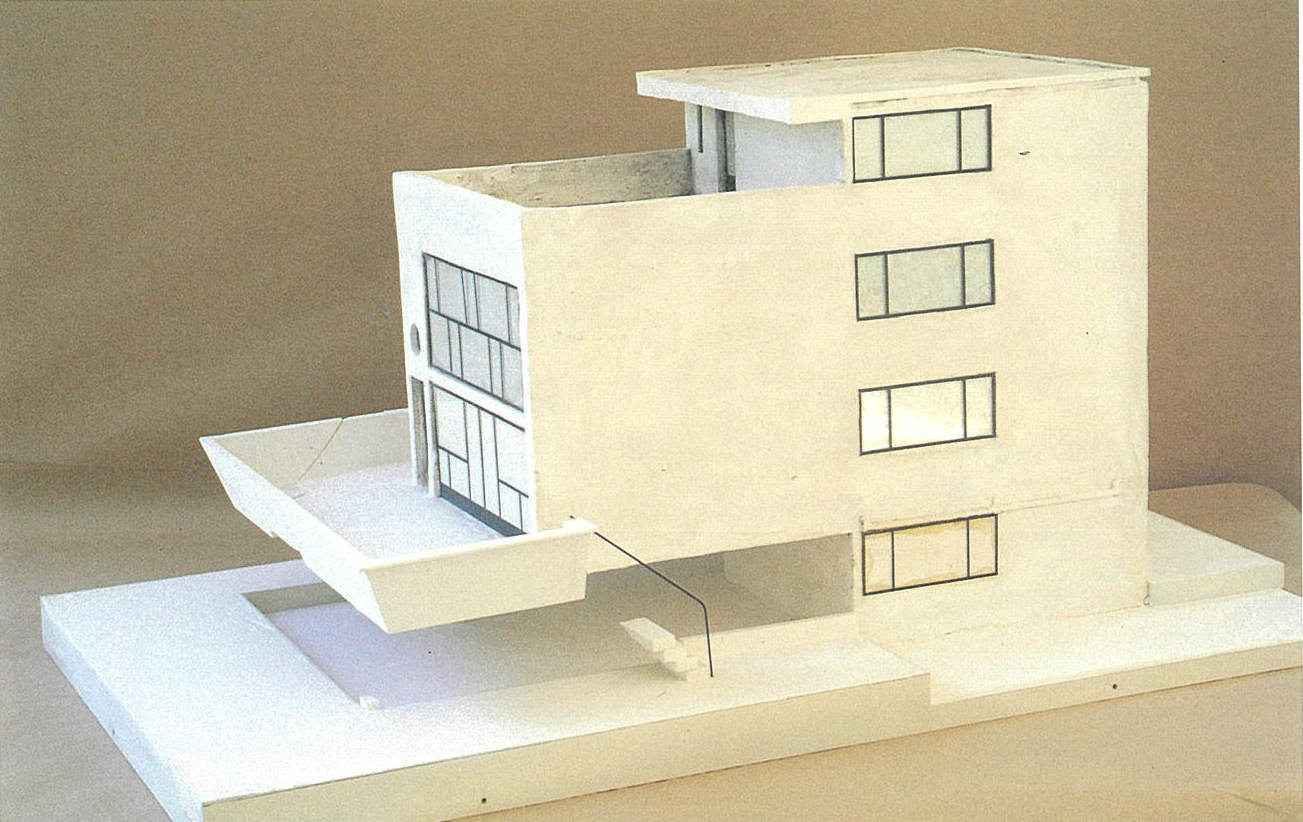

“Architecture is a panting in the convention.” Corbusier stated. And immediately after that he introduced the industrialized architecture “Citroan type mass-produced house” (1920). Of course, Citroën is a mess of Citroen. It’s a simple, bright, and easy-to-living house that has a white box shape with a colonnade, a large glass opening, and a roof terrace.

(* Maison Citroen, 1922, Source: “Le Corbusier Exhibition Catalog”, Mainichi Shimbun, 1996)

It might be just a coincidence that the1922 plan, which was an improvement on the first plan with the first floor raised by a piloty and used the lower level as garage, reminds me of a car.

“Think of house as a machine for living, and think of it as a tool.”

“Dont ashamed to live in a house without a pointed attic. It has smooth walls like iron plates and windows like the glass roof of a factory. But be proud, That means having a convenient home like a typewriter. ”

“Let’s show Parthenon and the car and let them know that they are products of selection, although in two different fields.”

(* Weissenhof Siedlung, 1927, Source: “Le Corbusier Exhibition Catalog”, Mainichi Shimbun, 1996)

The famous quote “Machine for living”

Machine meant a car. The house admired the car.

A never ending dream of car x housing. Kunio Maekawa’s “Premos”

The architect, Kunio Maekawa, trained for two years at Le Corbusier office. First Japanese member there.

“Premos” is a prefabricated house with wooden panels that Kunio Maekawa was involved in the design. It’s like an apostle of mass-produced houses in postwar Japan.

Maekawa was in charge of the “Minimal house” at Corbusier office at the which proposed by his teacher and became the theme of the 2nd CIAM competition. Premos was a post-war Japan attempted a building revolution with mass-produced houses and it inherted the will young Corbusier.

(* Premos No.7 explanatory drawing, Source: “Away from Le Corbusier”, Hiroshi Matsukuma, Misuzu Shobo, 2016)

Japan’s housing shortage after World War II, which was said to short of 4.2 million homes, was a serious issue at the time. And at the same time, the conversion of the munitions industry to civilian life was an important. As like it was in the United States and Europe.

《Premos》 PREMOS is a combination of PRE of prefab, M of Kunio Maekawa, O of Kaoru Ono, a junior and architect, and S of Sanin Industry Co., Ltd.

Maekawa, who was originally involved in designing a factory of large glider aeroplane manufacturer called Sanin Kogyo Co., Ltd during the war. Owner of Sanin consulted Maekawa how to use crafts man and machines from the company that lost jobs after the war.

The man behind Sanin Industry Co., Ltd. was Yoshisuke Ayukawa. Ayukawa was the founder of the later Nissan group which includes Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., and he was known to Maekawa before the war in the construction of an airplane factory in Manchuria.

Approximately 1,000 Premos were built, and they had some achievements as a product that involved architects in the early days of prefabricated houses, but most of them were for coal mining workers in Hokkaido and Kyushu. There were only a few regular houses. The post-war policy, which was a so-called slanted production method, that concentrated investment of resources in core industries such as coal and steel rather than housing and consumer products to promote economic recovery was a hindrance.

Another major obstacle was the lack of a sales system, which is the cornerstone of mass-produced housing. Of course, Kunio Maekawa was not interested in selling or having a route. In the light of its original purpose for housing-hungry people, Premos was far from successful.

Perhaps there was something in Premos that Ayukawa saw during the time of lack of housing after the war. but at the same time, Ayukawa was irritated by its sales and poor management. Ayukawa asked Maekawa to leave Premos to himself. Maekawa replied, “If you give Premos that to you, it will never be better” and the two took separate ways.

Terunobu Fujimori, an architect and architectural historian, laments: Kunio Maekawa, who represents the modernist architecture that received the scent of Corbusier, and Yoshisuke Ayukawa, who represents automobile manufacturing, met at the beginning of the postwar period. ”“ If that was the case, Maekawa was in Premos. “If I had given it to Ayukawa,” the postwar history of cars and housing in Japan may have been completely different.

(* Le Corbusier and Kunio Maekawa, source:https://www.pinterest.jp/pin/445926800594664152/)

People who know the secret story of “Premos” birth and frustration are not limited to Fujimori, and they can’t stop dreaming waht could have happend.

The predecessor of Toyota Home, a house maker, was a company called Yutaka Precon that Toyota Motor founder Kiichiro Toyoda started in 1950. For Toyota, housing has been an area of concern from the beginning. Toyota has continued to dream of housing since its founding, including the Misawa Homes that went bankrupt in 2005 under its umbrella.

The cars continues to dream houses.

text by Tetsuya Omura

* References:

Le Corbusier “Aiming for Architecture” (Translated by Takamasa Yoshisaka, Kashima Press, 1967)

Terunobu Fujimori “Showa Residential Story” (Shinkensha, 1990)

“Le Corbusier Exhibition Catalog” (Mainichi Shimbun, 1996)

Hiroshi Matsukuma “Away from Le Corbusier” (Mizusu Shobo, 2016)